A Note on Grief

Not even the hope of resurrection is a shortcut for the pain we feel.

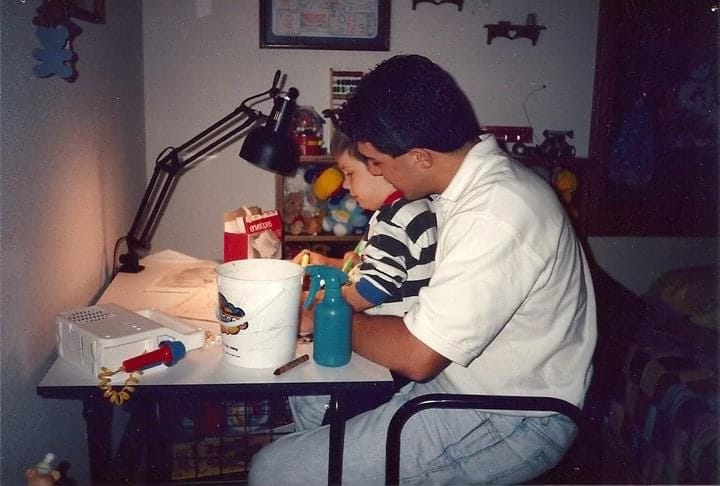

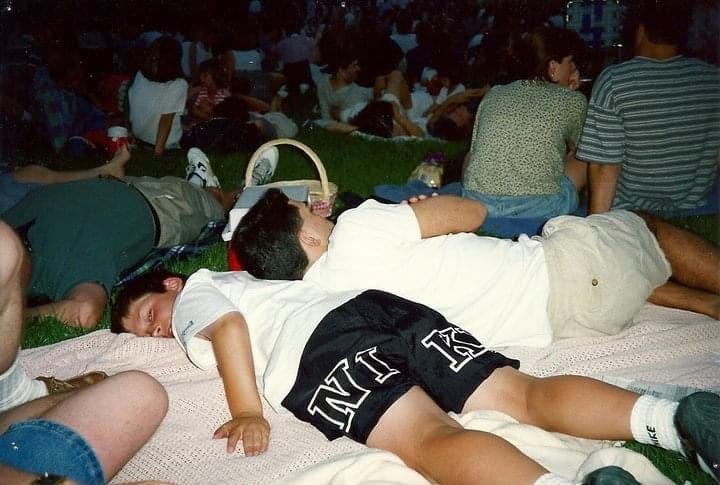

I did not see as much of my brother as I would have liked growing up. Given our 18-year age gap, he was out of the house by the time I could walk. As I progressed through early elementary school, Joe was either off in college or beginning a successful business career in San Francisco. I cherished my time with him over holidays and vacations.

Our family moved to Washington D.C. in 1997 when I was in the fourth grade. Around the same time, Joe began working on Capitol Hill for a state senator, a vocation which better aligned with his humanitarian passions. I didn’t know it then, but I would soon be making up for all my lost time with my brother.

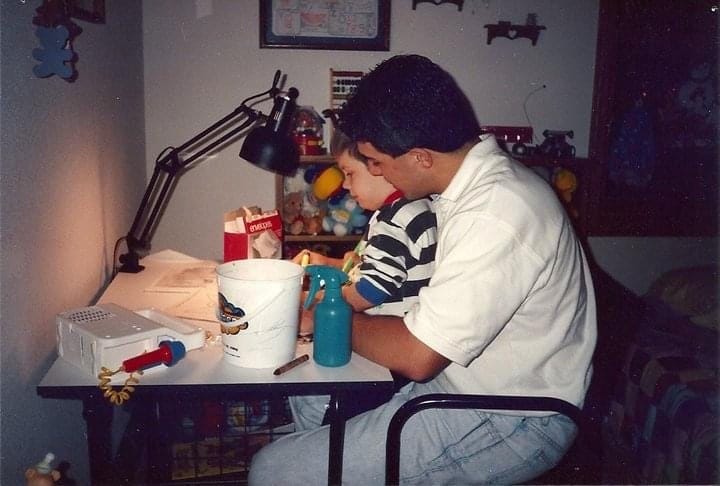

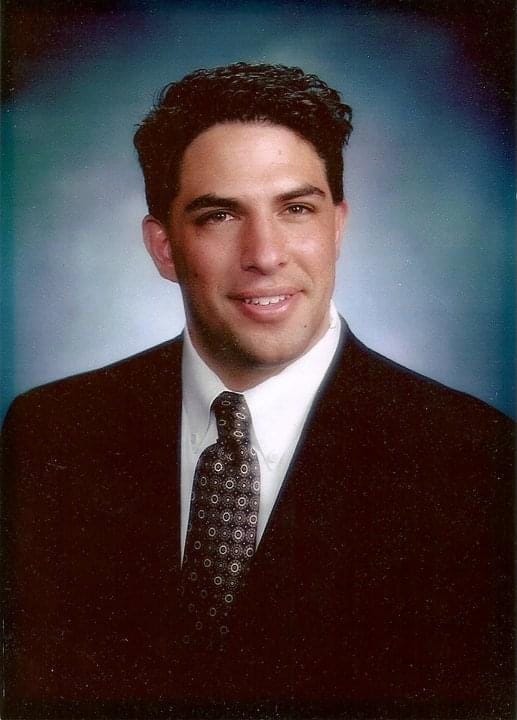

Joe was an attractive, successful, intelligent, 20-something guy. He had no business hanging out with his 10-year-old little brother. But he did – and that’s part of what made him so amazing! He pursued me. He took me on dates with him. He brought me to work. He came to my school events. He drove me around the city, teaching me about Star Wars and social justice. He showed me physical affection. We spent hours at Chuck-E-Cheese perfecting our skee-ball game.

He was the best big brother I could have asked for.

It has been 24 years since my brother chose to end his life. It is unthinkable that he has been gone for twice as long as I knew him. Every ache since that day has somehow been worse, every joy duller than it should be. Relationships are so much harder: it is more difficult to trust, more painful to open my heart up to others.

Like a planet that has lost its sun, life has – to this day – been colder, darker, and more aimless than it was before.

I recently shared a reflection on grief with our congregation from John 11:17-37. This well-known scene of Jesus by the grave of his friend Lazarus has transformed the way I think about grief and loss. Here we see Jesus coming to the grave of this friend whom he dearly loved. He knows what he is about to do – he has set himself toward raising Lazarus from the dead (vs. 23). Even so, Jesus is not cold, calculated, or stoic about his friend’s loss. As he sees the pain of the people, as he nears the site of his friend’s body, Jesus is overcome with emotion. He is angered. He mourns. He collapses in grief.

He weeps.

The Son of God, the resurrection and the life, is overwhelmed with sorrow. In his example, Jesus demonstrates for us that there are no shortcuts for our grief – not even the hope of resurrection.

For the longest time, I believed that the gospel ought somehow to lessen the pain and grief I feel. After all, aren’t I supposed to be one who grieves in hope (1 Thess. 4:13)? Hasn’t the sting of death been taken away (1 Corinthians 15:56-57)? Isn’t grief a sign, then, that my faith is weak?

I realize now that I had it all backwards. The gospel does not take away my grief – the gospel intensifies it. We grieve in hope not as we suppress our pain with cheery platitude, but as we courageously follow Jesus into the depths of grief and loss. We need not fear the sting of death, but we also must not run from it.

As we live between the resurrection of Jesus and the resurrection of the dead, we sit with Jesus by the grave, and we weep. It is here, at Jesus’ side, where I have learned what it means to really grieve. His tears wet my dry eyes as I am given permission to allow my tears to full more freely, more deeply, more truly, than I ever have before.

Sitting with Jesus has given me permission not only to persist in grief, but to acknowledge how it changes and affects every area of my life. After losing my father three years ago, grieving my brother’s suicide has been more difficult than ever before. I was at home with my father when he discovered my brother’s body. I remember the sight of my father collapsing in grief as his body heaved. I remember his screams as he called 911. It was the darkest moment of my life, one that only my father and I shared.

There is something sacred about sharing dark and painful moments with someone else, a concept I still have trouble articulating. I am alone now in that memory, however. What once felt vivid in my mind now feels more like a vapor. It feels less tangible, less real. A sacred tragedy shared in history is now held only by me. A burden I once shouldered with my father is now carried forward by one for the remainder of this life’s journey.

My sister passed away a few weeks ago. Because our relationship faded and strained in my adulthood, her loss has been difficult to grieve. But now, on this 24th anniversary of my brother’s suicide, I feel my grief evolving once again. What if my brother had not taken his life? What would my relationship with my sister have been like? What would her life have been like? How would things have been different? Better?

Questions with no answers that will haunt me until my journey home is over. Thank you, Jesus, for giving me permission to ask them. Thank you for weeping with me as my tears flow freely once again.

I have been greatly helped by these words from this prayer below. It is taken from a collection of prayers in Every Moment Holy Volume 2: Death, Grief, and Hope. The prayer is titled “Abandoned by One Who Chose Suicide” and it can be found either in the book or for a small purchase in their phone app. This prayer has given me words to pray these last few years, opening my heart to grieve in ways I never had before. I invite others who know the unique pain of suicide into praying this with me.

You know our grieving is far from over, O Lord.

You know our healing is incomplete.

You know we are not whole.

Though the initial shock of loss

subsides in time, the aftershocks endure,

and we must perpetually reckon the cost.

For it is a compounding harm,

tallied across every meaningful moment—

good and ill alike—in which

we must learn what it means

to wrestle anew with the nuances

of all these empty spaces;

empty because the one who should have

been here to labor, to lament, to console,

encourage, or celebrate with us is,

by their own choice,

so conspicuously absent.

I feel forsaken by one in whom

I placed great trust, O God.

I know a deep loneliness

no other soul can touch, like a pit hollowed

beneath the foundations of my existence,

an ever-present void into which it seems

my whole world might crumble.

I find it harder now to love,

and to let myself be loved,

as my instinct is to duck and cover,

run and hide, or scratch and fight

against the very compassions I need,

for fear of letting another near enough

to pierce my heart again.

And yet I know, if left unchecked,

these ripples of resentment will eat away

all future joy in life,

as surely as the slow workings of rain and rust

will flake and crumble iron.

But for your merciful,

tendering work, O Christ,

our hearts would finally be hidden

beneath impenetrable gnarls of scar tissue,

unable to give and receive again.

So let me now—and every time

such emotions arise—address them

before they perform their malignant work.

Lead me by your Spirit

to weed this field of heart and mind and soul,

lest it be overgrown and choked

of all that is good.

I offer to you, O God, these hurts,

and all other sufferings

that the enemy of my soul

might intend for evil and harm,

so that such wounds would not

render me brittle, but rather more supple,

as you—a potter watering and working

a soft clay—tenderly fold and smooth

such sorrows into the better design of

your vessel. Shape me into a reservoir

of your glory, your mercy, and your love.

Amen.