I recently caught up with a friend over coffee. He is a good man who stewards his financial resources and his vocation for the sake of others. My friend is now working toward a career change, making great sacrifices to himself, so that he can contribute more to the work of justice in our city.

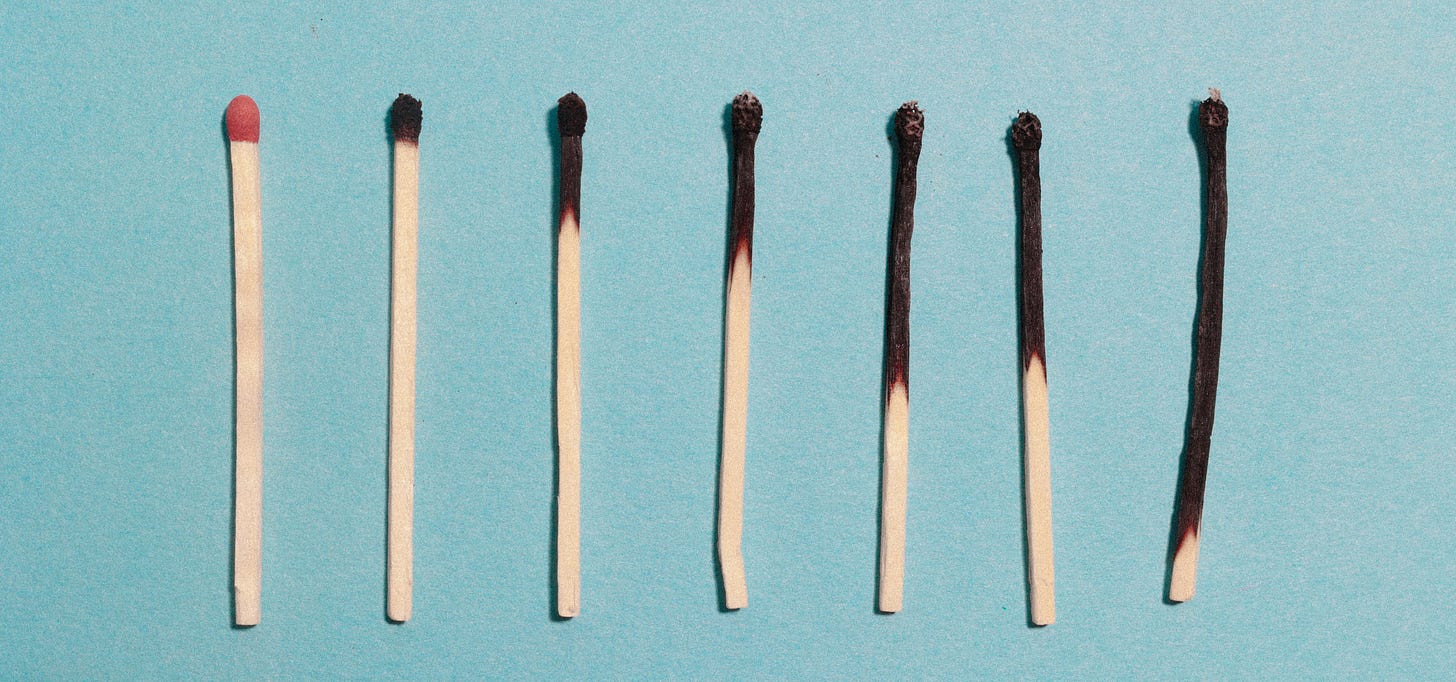

As our conversation shifted to social issues in our city, my friend recalled a previous situation that still weighed heavily on his heart. He had done his best to work toward justice and reconciliation across differences. Yet, he lamented, it “felt like the goal posts kept moving” for what was required of him. In other words, his efforts were never enough. Though this situation occurred years ago, it was clear to me that recalling these events still made my friend sad and tired.

I have written in previous posts about how Christians need to be doing more as advocates of justice in our communities. Many Christians do need the mercy of Jesus to melt their stubborn and selfish hearts. Many Christians do need to make radical changes in the way they steward their time and money. Many Christians do need to open their eyes to the oppression afflicting their neighbors all around them.

The Rich and Poor in God's Economy

What if a different approach to Jesus’ teaching could invite us into a new way of seeing our money and the relationship between the rich and poor in God’s economy? What if there is a way for us to reconcile Jesus’ real demands on our money and his deep compassion on the burdens of the wealthy? I want to suggest that such an approach to Jesus’ economic ethics does exist and that it has the power to move those with means out of the theoretical and into proximate relationships with the poor and suffering.

But this essay is not for those Christians.

This essay is for the burned-out ones; the good women and men who, despite their service to others, are burdened by the thought that they’re never doing enough. God sees your efforts and they are not in vain (1 Corinthians 15:58); he will not neglect the love that you show to others (Hebrews 6:10). Your good deeds are a reflection of your Savior, and in him you have peace (1 Peter 2:11-25).

The Ministry of Christian Benefactors

I regularly speak with Christians who feel guilty about their wealth and social position. They wonder why God would choose to bless them with such gifts when so many people suffer. I’ve heard many Christians wonder aloud if they should be forsaking their resources, their vocation, or their homes, so they enter into solidarity with the poor and oppressed.

Maybe some of you should. It is unbecoming of any Christian to live a life of luxury or comfort without a critical examination of their excesses.

Yet, the poor and oppressed will be no better off if most Christians with wealth and social position give it all up to fulfill their notions of “solidarity.” Instead, Christians with means should recover Scripture’s teachings concerning the role of benefactors in the church and in broader society.

Recent historians, such as Rodney Stark, have reexamined the common assumption that Christianity primarily grew among the lower classes of society.1 While it does appear that Jesus found most of his followers among the poor, Christianity could not have spread without its influence upon the wealthy and influential in society.

In his book Seek the Welfare of the City, Bruce Winter situates many New Testament passages within the social context of Greco-Roman expectations regarding civic benefactors. Wealthy citizens of Greek cities were expected to give substantial gifts to benefit the public good frequently. These gifts included supplying extra food and grain, selling goods in the market at a discounted rate, contributing to the construction of new public buildings, refurbishing or building city infrastructure, advocating for the city in their respective spheres of influence, and providing aid during moments of upheaval. In short, the wealthy were expected to steward their resources for the benefit of the community rather than keeping them all to themselves.2

When wealthy and influential citizens converted to Christianity, they would not have been exempt from fulfilling this customary role.3 In fact, based on clear arguments in Scripture, wealthy Christians were expected to go beyond existing civic expectations. Peter’s first epistle is a great example to us here. As “elect” citizens scattered throughout the Diaspora (1 Peter 1:1), God’s people were called to do good in light of the knowledge that Jesus Christ is returning (1:13-17). In light of this future hope, Peter called God’s people to declare God’s splendor through their good works (2:9-17), to follow Jesus in the face of suffering (2:21-25), and to bless others by returning evil for good (3:9-14). These acts are intended to be observed in public so that God would be glorified (211-12).

As Winter summarizes, “1 Peter holds together two crucial, but related biblical doctrines, eschatology and social ethics. To stand in the ‘true grace of God’ demanded a deep commitment to the welfare of the city within the framework of a living eschatological hope.”4

Winter convincingly argues that Paul’s language about “doing good” in places like Romans 13:3-4 echoes 1 Peter and is likely an appeal to the civic benefactor customs of Greco-Roman cities. Like Peter, Paul renewed and elevated the call for members of the church with means to excel in benefaction in light of their hope in Christ.5 That the instructions in such passages are typically in the singular rather than the plural gives credibility to the argument that Paul was appealing to a smaller group of wealthy individuals in these congregations rather than the church as a whole.

Here's the point: there is no place where God gives a universal command for the wealthy and influential to forsake these gifts. Instead, he charges us to use these gifts for the good of others. If you’re regularly examining your resources and striving to make use of them for the sake of your vulnerable neighbors, then you’re doing exactly what God wants you to do, and that is enough. Thank you for modeling how we should all be stewards of our skills, talents, resources, and social position on behalf of those who are vulnerable and oppressed.

Living as Faithful Stewards

In their book Buried Seeds: Learning from the Vibrant Resilience of Marginalized Christian Communities, Alexia Salvatierra and Brandon Wrencher tell a powerful story that illustrates this principle:

A lawyer came to a community to join with the poor, and to learn from them what it meant to belong to a truly Christian community. Over the years he came to love the people more and more. He began to identify with them to the point that he was bothered by his middle-class status. "I do not want there to go on being this division between us," he thought to himself, "that I am a well-paid lawyer while they are poor bricklayers. I must be brave enough to cross that boundary and accept the same humble position. Then I really will be able to say I am their brother." He went to the community and told them of his decision. "I am resolved," he explained, "to give up my job and my position, and to become truly one with you. I will learn bricklaying from you, and so become more fully a member of your community. I believe that is what God is calling me to do." But as he spoke he saw some hesitation on their faces. He had expected them to embrace him with joy, but instead they held back and were whispering among themselves. "One moment," they said. "We need to have time to talk about this. Please wait while we go away to discuss it." When they came back from their discussion, their faces were still grave. "If this call has truly come to you from God, we will not stand in the way. We must not oppose the will of God. But we have a problem. We need a lawyer. Who will give legal help to us poor people if you are no longer a lawyer? We have talked together and reached a decision. On the day that you leave the law to become a bricklayer, we will choose one of our number to study the law in your place."6

You’re no good to your vulnerable neighbor if you’re burned out or if you forsake your resources, your skills, or your social position. Who will steward influence on behalf of the marginalized if not you? Don’t quit your day job! God requires you to continue using these gifts for their sake rather than your own.

Here is how I’ve seen this faithfulness in the lives of some people around me. I see meaningful advocacy can be found in the exhausted mother whispering silent prayers for the battered women on her street as she takes care of her children. I see justice in the doctor who is fighting tirelessly for his immigrant patients. I see mercy in the woman who faithfully dedicates many hours each week to serve her immigrant neighbor. I see compassion in the teacher who is choosing rest so he can give his best to his vulnerable students when classes start up again in a few weeks. I see solidarity in the young man choosing to move into the neighborhood that everyone else seems to be running from. I see liberation in the church member who writes a check to their church’s deacon team that no one else will know about.

Do not dismiss the impact of the quiet life that is stewarded in love for vulnerable neighbors. These moments will never make the news, and they probably shouldn’t end up on social media. But this is how Jesus said the Kingdom would break in: through the small, unexpected, faithful actions of his people.

Jesus does not need rock stars and lone rangers, just faithful disciples who commit to a faith that works itself out in love.

And if that’s you? Well done.

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity, Chapter 2. See Also Stark, The Triumph of Christianity, Chapter 5.

Bruce Winter, Seek the Welfare of the City, 37.

Winter, 33.

Winter, 19.

Winter, 33-40.

Alexia Salvatierra and Brandon Wrencher, Buried Seeds, 93.