I recall sitting in the back of the car as a boy while my family drove down the highway. I was struggling to read the road signs ahead. I remember feeling confused because I didn’t think it had always been so challenging to read these signs. I shrugged off my confusion, believing that my vision must have always been this way.

It wasn’t until months later that I had a standard check-up with the optometrist. As it turned out, over the previous 12 to 18 months, my vision had gradually deteriorated. It happened slowly enough that I didn’t really notice what had happened to my eyesight, but significantly enough that I had been increasingly confused by why I was struggling to see. My fuzzy vision had become my new norm, even if it was perplexing.

Only after putting on glasses for the first time did I remember what the world was supposed to look like.

My tradition has a rich legacy of social activism and justice, powered by the ministry of deacons (or the diaconate). We know that the diaconate is more than an optional tagalong for local congregations. Deacons are an essential component of the church and a foundation of our social vision. Their ministry leads the Christian community into being a doing people (James 1:22), people who press deeper into Christ's heart and administer his compassion for the strengthening and building of his church.

The Necessity of Deacons

Deacons are the heart and soul by which our commitment to Christ’s love, mercy, and justice rises or falls. By examining five theologians across multiple generations of the Reformed tradition, I will show that an elevated diaconate is an essential feature of the Reformed tradition. Following this examination, I will conclude with brief thoughts on strengthening the diaconate and empowering works of mercy and justice in our local churches. While I am spending my efforts in the Reformed tradition exclusively, these words are for all those who want to strengthen their deacons and recover a vision of mercy and justice in their local church.

Deacons have historically been responsible for strengthening schools, serving in hospitals, alleviating poverty, ministering to prisoners, orchestrating immigrant aid, and caring for any victim of the unjust social order.

Yet over the last century, our churches have gradually lost their vision for the diaconate. Culture wars and denominational splits over doctrinal purity have led to a focus on doctrinal knowledge, rather than obedience from the heart, as our highest good. Neoliberal capitalism has infiltrated our theological presuppositions, resulting in a highly individualistic religion that promotes upward mobility rather than service that moves down and out to the margins.

I know I am not alone in my experience of confusion within churches and their frequent neglect of social concern. All of this great theology has led you, like me, to the conviction that our churches must be guardians of the poor and oppressed. We know that Christ will test our churches based on our commitment to justice for the weak (Matthew 25:31-46). Yet, we look around, and such commitment appears increasingly rare. We feel alone in our convictions.

What are we supposed to do?

My work on this platform aims to help us put on our theological glasses so we can remember what our social vision for the world is supposed to be. Though our vision may be blurred, restoring the diaconate to a place of prominence will help us see how our churches can minister our King’s justice.

If you care about social justice, then support your deacons. The diaconate embodies the most honorable form of service to King Jesus that every Christian should desire to follow and emulate. Deacons ensure that justice is given in God’s name, rather than our own. Their ministry is a powerful witness to the world, serving as a tremendous force for good in our communities. More importantly, when the congregation supports its deacons, they bring great honor to Christ.

Justice and the King’s Royal Service

One of the great champions for a robust vision of the diaconate was the Dutch theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920). His work has a significant influence on this essay, and I believe it should also have a profound impact on our churches today.

In his essay “Philanthropy,”1 Kuyper summarized how the churches had allowed care for the poor and the oppressed, which he simply referred to as philanthropy, to become a matter of individual concern rather than a primary task for the Church. As the church weakened in its philanthropic task, private initiative “sprang into action.” While people may have merely wanted to assist the church at first, because of the “church’s sluggishness,” people soon “tried to cut [the church] off entirely from philanthropy,” and instead placed the philanthropic task squarely on the shoulders of the government. The churches obliged and abandoned their philanthropic task.

Before the churches can take back the task that properly belongs to them, they must first “become conscious once again of the [philanthropic] obligations it has toward the King.” Kuyper beautifully illuminated how Christ is the consolatory “in the spiritual as well as the physical sphere.” Sin does not merely affect spiritual matters, but “was necessarily accompanied by human misery.” As Christus Consolator, Jesus addressed both spiritual sin and the resulting physical misery “in order to break the work of Satan.” Kuyper’s moving words are worth quoting at some length:

There is no doubt that the spiritual is and remains the starting point, but by placing his opposition to our human misery in the foreground, Jesus does demonstrate that we would be doing his honor a disfavor if we were only to honor him as the one who announces the gospel, and that we only give him the honor he deserves once we venerate him for saving us from both sin and physical misery. The one may not be disparaged in favor of the other. The two go together. It is only by paying attention to both of them that you will understand the Christus Consolator in all his fullness.

In taking back the philanthropic task, the church must repent of how it had “impoverished itself in its offices” and “presented itself as an exclusively spiritual institution.” This “regression” caused “serious damage to the honor of Christ’s kingship in his church.”

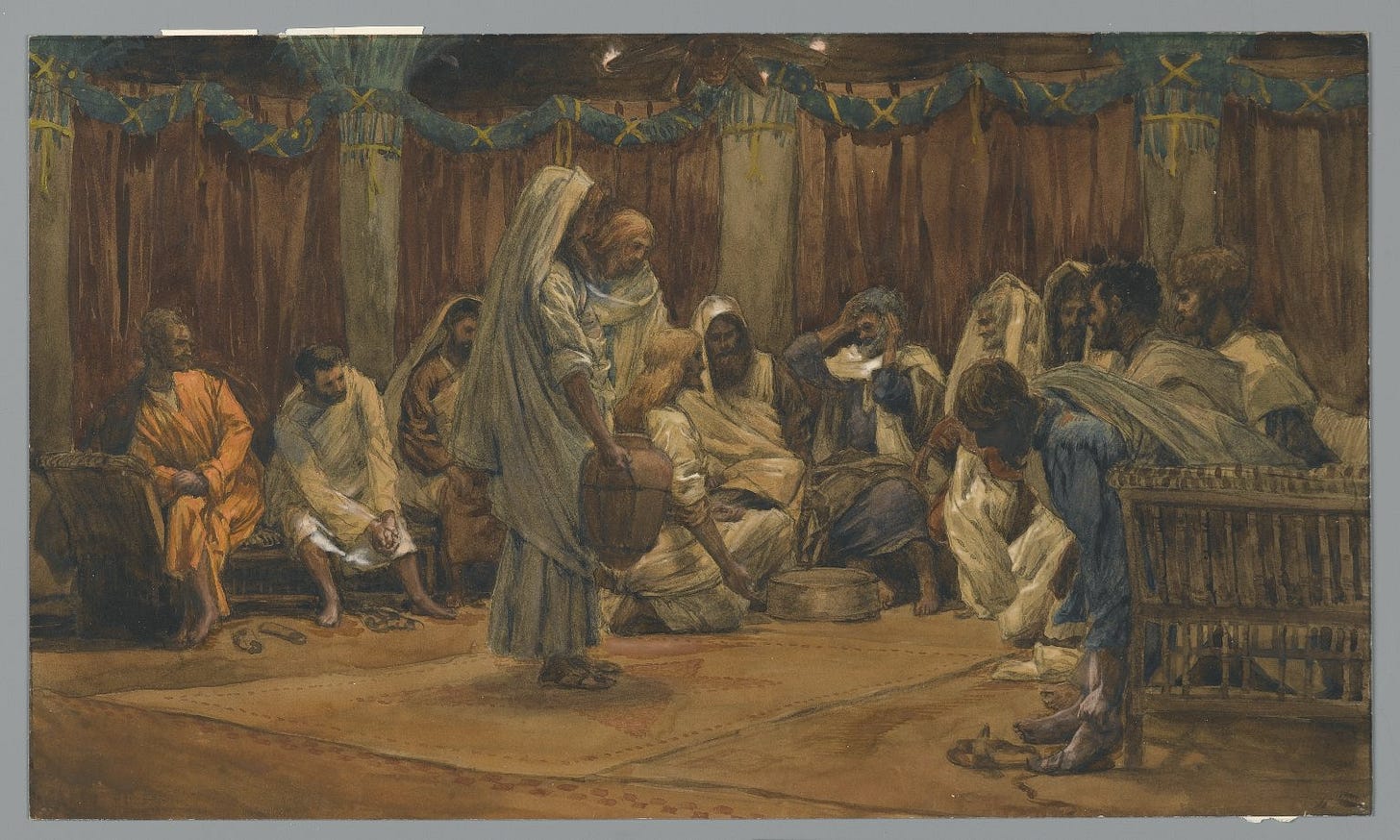

It is in this relationship of Christ the King to the Church that the deacons must reposition themselves. If the Church only brings honor to their King when they address spiritual as well as physical misery, then the responsibility of the diaconate is a noble task. Because they are embodying the service of a King who is the great Consolator, deacons are a “kingly office” who exercise Jesus’ royal service to his people. Bringing the consolation of the King to his people makes the deacons the most “honorable form of aid given in Jesus’ name.”

Justice in the King’s Name

In his revolutionary book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Brazilian educator and liberation theorist Paulo Freire criticized how liberal notions of justice often perpetuate paternalistic relationships within an oppressor-oppressed hierarchy. As Freire observed, many who work for justice are merely rationalizing their guilt “through paternalistic treatment of the oppressed, all the while holding them fast in a position of dependence.” Such a person depends on “pious, sentimental, and individualistic gestures” toward the oppressed but resists true solidarity, because they instinctively want to maintain distance and separation from the poor.2

Abraham Kuyper’s work helps us understand that, rightly exercised, the diaconate resists this faux imitation of paternalistic “justice,” drawing the rich and poor into mutually dignifying relationships of solidarity and reconciliation.

Twelve years before his words in “Philanthropy,” Kuyper was actively engaging at the civil level in his second term in Parliament. In 1895, Kuyper proposed a comprehensive pension plan for the working classes.3 His plan was an attempt to address poverty in both the short term, through temporary aid, as well as in the long term, by improving the overall moral infrastructure to better care for the aging population.

In Kuyper’s view, the government should not be permanently tasked with poverty alleviation. Yet, when poverty spreads and “philanthropy falls short and starvation is imminent, government inaction would be criminal.” The government needed to step in to alleviate the poverty of the working class, but should only do so as a temporary measure, with the goal of restoring this task to its proper place:

The churches.

As he would later lament in “Philanthropy,” Kuyper observed how the churches had allowed the diaconate to “slide” and perform its task “perfunctorily.” The significance of the deacons’ labors needs to be restored, for it is the charge of the deacons not only to care for the poor in the churches, but also “the poor in general.” Kuyper named immigrants as those who should “particularly… enjoy the benefit of hospitality.”

Kuyper explained how the diaconate is crucial to God’s design, so that justice may be served in his name. Deacons are “the expression of the morally elevating thought that help and care for the needy do not come from human beings but from God.” What the rich possess does not belong to them; their wealth belongs to God, and it is the responsibility of the rich to steward it as God intends.

On their own, the wealthy may give generously to the poor or to charity. Yet, when God is left out of the picture, human beings are “giving of their own money.” The money is given in their name, not God’s. Kuyper observed how the wealthy thus often become “pleased with their own generosity and pride themselves in it.” The result is that the poor are humiliated and become beholden to the rich. Hierarchies are imposed on communities, dividing them between the haves and the have-nots. This cycle of paternalism only perpetuates the injustice.

Through the diaconate, God’s design is that the wealthy would give their money to the poor “without revealing their name.” When the wealthy transfer their money to the deacons, their wealth remains “strictly God’s money,” and the poor then receive money in God’s name, rather than in the name of wealthy individuals.

The Rich and Poor in God's Economy

In God’s economy, the rich and poor are brought together into a new reciprocal relationship where each relates to the other out of unique care and concern rather than hostility and separation.

This system shows “love in the most delicate and least self-serving manner.” The poor are not humiliated and do not become dependent on anyone. The needy “receive their alms from the same God from whom the rich man receives his wealth.”

Deacons, then, are God’s instrument for keeping the rich and the poor dependent on God alone. In their shared dependence, the class walls between the strong and weak come down as they are restored to affectionate solidarity.

Justice and the King’s Honor

Deacons are a foundational component of the Christian social vision. Jesus intends to build his kingdom by meeting people’s needs through the witness of his church.

How can the leaders and members of a local congregation start investing in their deacons according to the measure that God requires of us? I offer a few thoughts on how we can begin restoring our deacons—and the King’s honor—in our churches.

Church leaders must intentionally consider how to fund the work of the diaconate. At minimum, the deacons should be financially supported in three ways: 1) through funds set aside from the church’s general budget, 2) through special offerings throughout the year, and 3) through the option to give directly to the deacon fund.

Local churches should invest resources in training the diaconate. Typically, continuing education and conference funds are reserved for pastors and elders. Deacons must also be equipped through workshops, seminars, conferences, and other similar opportunities.

The work of the diaconate should be regularly communicated to the congregation. A “mercy month” is a great start, but it is only that. How can the ministry and needs of the deacons be regularly communicated on Sunday morning? Is there a deacon who could preach once or twice a year on God’s heart for the poor and oppressed? Could the deacons create their own newsletter for the congregation?

There are many good philanthropic causes that Christians could give their money and time to; deacons should never feel like they’re having to compete with any of them for congregational support. Our members should see the diaconate as their first philanthropic commitment.

Church members should engage frequently and liberally with their deacons. Do not wait for the diaconate to approach the congregation with needs or opportunities. Start setting aside additional funds for your deacons now. You don’t have to be wealthy to provide regular support and encouragement.

Let your deacons know how you’d like to serve. Email them with your skills and experience. Do you want to serve as a reading mentor? Do you have experience working in an after-school program? Could you donate your skills as a financial advisor, lawyer, or educator to those who need them? What new initiatives would you be willing to help lead with the support of the diaconate?

Finally, when the deacons tell you they have a need or ministry opportunity, show up! Deacons should never have to beg for financial support or volunteers. Deacons are officers appointed by God for his glory and your good. Follow them!

Abraham Kuyper, “Philanthropy” in Pro Rege 2:281-288.

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 49-50. See also page 79ff for another critique of paternalizing liberalism.

Abraham Kuyper, “Draft Pension Scheme for Wage Earners” in On Business & Economics, 234-252.

The apostles in the Acts situation could have very easily just dispatched a few more rations to the minority widows. Or told them to stop complaining, dividing the church. Or perhaps they would have done the American solution: Dispatch the minorities to take their meager resources and their widows and “go plant an ethnic church across Jerusalem, or across the street”. They did none of those easy solutions. Instead they very wisely instituted the Diaconate, to ensure justice in the camp. And the church grew. And the model was prescribed for other city churches.

Wouldn’t we love to see a collaborative group of City Deacons to ensure justice in the camp?

In the OT, there was a second tithe taken every three years that was completely for the work of serving the poor. Using that as a benchmark Christians giving 13+% of their own increase would allow each church to budget 25% of the overall giving for mercy ministry for the sake of the poor.