Leadership is Not a Platform

Resisting temptations for selfish gain at the expense of those we serve.

It is hard for me to trust other leaders, but that is probably not their fault.

I can still remember sitting down at my computer nearly 15 years ago to try to do some internet sleuthing on my late brother Joe Hein (1970-2000). I had a renewed interest in finding any kind of documentation that would tell me more about him, including his political and humanitarian work. I entered some basic details about my brother into the Google field and hit the ‘search’ button, not knowing what I might find.

A Note on Grief

I did not see as much of my brother as I would have liked growing up. Given our 18-year age gap, he was out of the house by the time I could walk. As I progressed through early elementary school, Joe was either off in college or beginning a successful business career in San Francisco. I cherished my time with him over holidays and vacations.

Page after page, I pored over the results. Most links had nothing to do with my brother but were about other South Dakota politicians or men named Joe. I remember reaching well into the mid-20s of the page results before I found the link I didn’t know I was looking for.

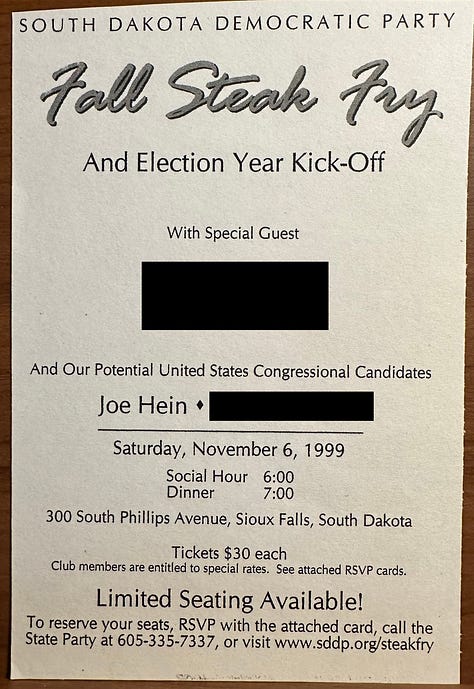

On an old archived server of political communication, I stumbled upon an email exchange about my brother Joe from November 1999, about five months before he took his own life. The emails were exchanged among various aides on Capitol Hill, discussing my brother’s political aspirations to run for state representative in our home state of South Dakota.

This communication trail became a window into the last months of my beloved brother’s life. I want to be clear: I point no fingers and blame no one else for my brother’s death (though I have pointed the finger at myself—perhaps that is an essay for another time). He struggled his whole life with undiagnosed mental health challenges, likely some form of bipolar disorder. I share these details not to point blame but to identify formative lessons in my own leadership journey.

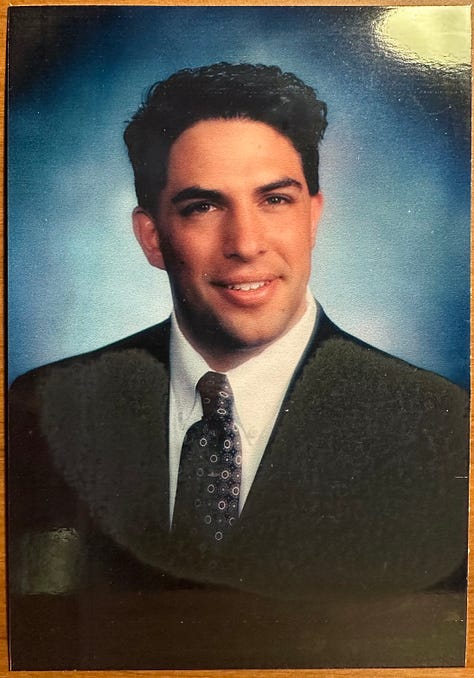

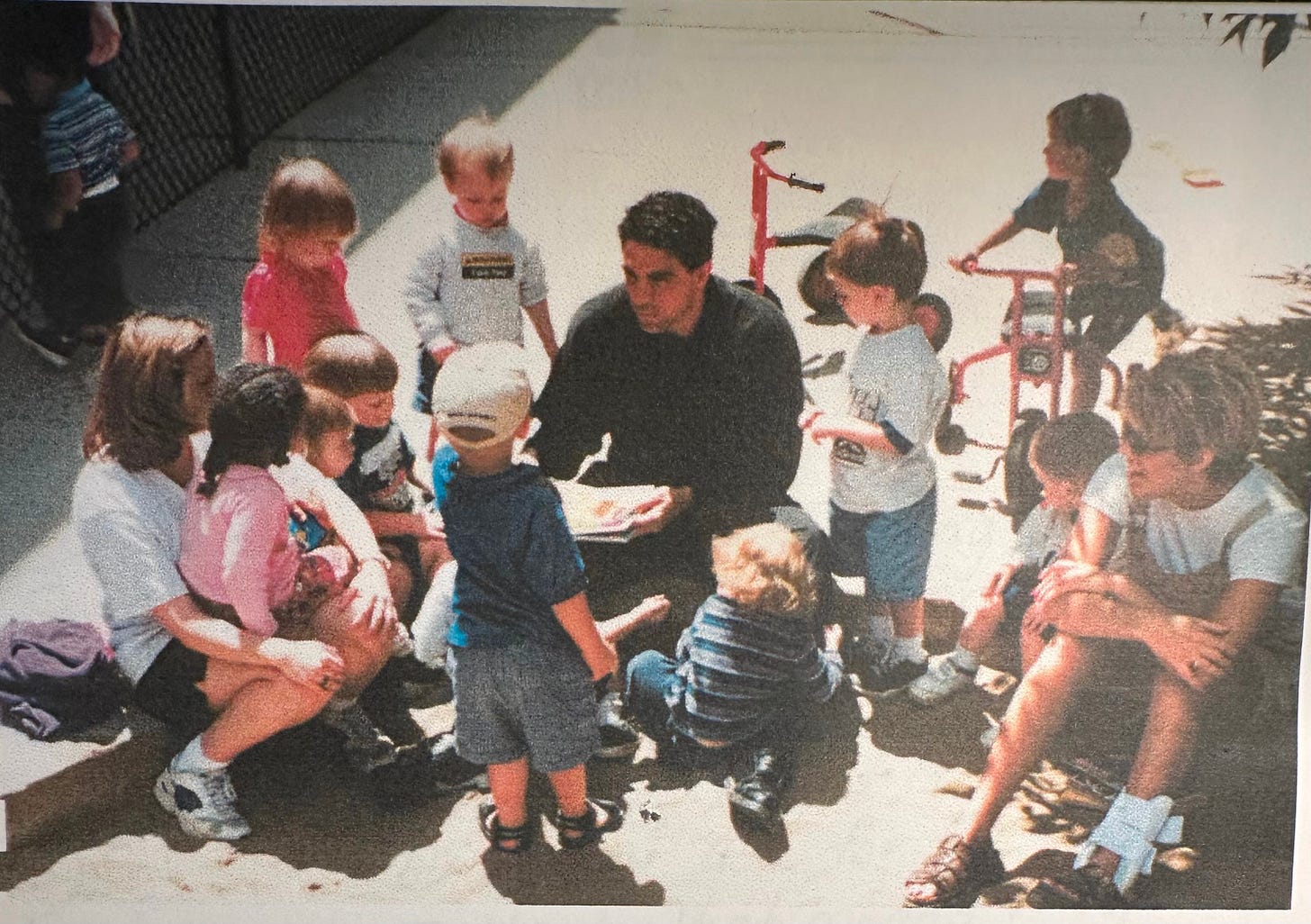

I found comfort in this document. These aids praised my brother. Ten years after his death, it was affirming to know that his colleagues and superiors saw him as I remembered him. They described him as bright, energetic, and photogenic (see for yourself!). They acknowledged his community service, humanitarian work, and non-profit initiative, Everybody Wins!, a program to help elevate the reading abilities of disadvantaged youth.

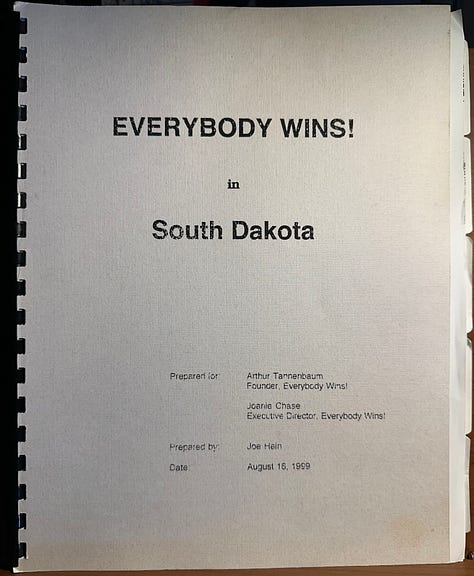

In the fall of 1999, Joe intended to expand Everybody Wins! while also beginning his campaign for state representative. Sometime between August (see the picture of his proposal here) and December (when he came home for Christmas completely depressed), Joe realized that he would not be able to secure the funding needed to expand the program as he desired.

In the wake of that defeat, this document also revealed the opposition that my brother faced in pursuing his political dreams. The leaders on Capitol Hill acknowledged that while my brother possessed many positive qualities and had accomplished significant work, he was not yet a viable candidate to win political elections. They agreed to meet with him in November to collectively close the door on a run for office. He would not gain support from the national Democratic Party.

For some reason, they agreed that Joe’s real potential as a candidate was not “a subject that you should raise [with him].” I try not to overanalyze this comment (why wouldn’t you want to affirm his political gifts if you knew he had them?). Instead, they decided to tell him that his “age and timing are disadvantages.” They wanted to advise him to emulate another state representative, whose political and non-profit work became mutually beneficial to her own “increased profile.” Their advice to him was not to pursue the political office but to continue focusing on building his non-profit until he could establish himself as a viable “up-and-comer” for political candidacy.

In other words, play the political game, and maybe we’ll let you in the door.

When my brother came home for Christmas in December 1999, he was different from how I had ever seen him before. He was quiet, sad, and withdrawn. I see now that he wasn’t just fighting mental illness; he was also suffering from a broken heart. When I first shared this document with my father, he responded, “If it was suggested that he give up his dream of running for Congress, along with not getting enough funding for Everybody Wins!, I think it could have contributed significantly to his depression.” Despite years of pouring himself into service to his community, he was told he had to play the game, and that game crushed him.

I wonder what broke my brother’s heart more: being told no, or the realization that he would have to play a game he had no desire to play?

The most significant lesson I’ve learned while reflecting on this document and my brother’s legacy is that leadership is not a platform. Service is not a game to win for one’s own advantage. Leaders should not serve a group or community to gain an “increased profile.” We don’t serve to ascend the ladder of politics and influence but to lower ourselves for the sake of our neighbor.

I carry a chip on my shoulder because of how my brother was treated. I tend to be skeptical of other leaders. I know there is a game to play. Are you playing it? My skepticism has often proven valid, as I’ve seen many non-profit leaders, politicians, and pastors accrue great power in the name of service, social justice, and ministry.

In his introduction to Paulo Freire’s The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Donald Macedo uses Freire’s work to criticize the political careerist who uses “slogans, communiqués, monologues, and instructions” about justice to merely advance their own career. Such individuals are not committed to a life of praxis with the suffering, but instead will happily stand on the backs of the suffering to further their own careers in academic and political institutions.1 As Freire noted in his book, such behavior is, at best, condescending paternalism. At worst, those who use service to their communities to build their platforms and influence rely on the dependence of the suffering and thus, in the name of justice and service, become oppressors themselves.

But my skepticism is not just due to my wariness of the games people play to get ahead. I am also aware of the temptations and dark desires within my own heart. I often hesitate to trust other community leaders because I am reluctant to trust myself.

I remember a lunch meeting with a close friend four years ago, as our family was preparing to move to Indianapolis to begin cultivating a new church here. Toward the end of our conversation, my friend said he wanted to ask me a direct question. “Ben, I’m sure many people want to talk to you about whether you’re prepared for this endeavor to fail. I want to ask you, are you prepared for it to succeed? How will you steward the attention, influence, and power that come from a successful ministry?”

I think about his question often. Over these last four years, I have become painfully aware of my secret desires for recognition and influence. Selfish parts of my heart want this new church to “succeed” so that I can move up the ladder of various social, academic, and Christian institutions.

I want to be recognized. I want power. I want influence. I want more.

Yet I hear the words of Jesus echoing loudly in my ears: “Not so with you” (Mark 10:43). The way of Jesus does not define greatness as self-assertion or self-display but as self-effacement. True greatness remembers that it was the heart of Jesus to empty himself in service, not to assert himself and grasp for more power (Philippians 2:5-8). We find life in Jesus not because he wanted to make a name for himself but because he poured out his life for us.

Leadership, if it is to mean anything at all, must be defined by self-denial for the sake of others. Those called to lead must make every effort to resist the game of influence and self-advancement. We must die to selfish desires every day.

Manipulation that masks selfish gain as service will be the death of the people we are called to serve.

Only loving service expressed in humility by those who empty themselves for others can bring life.

Donald Macedo, “Introduction” in Paulo Freire, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 8.

Thank you for sharing these wise and personal reflections, and for allowing us to know a bit about your brother. He sounds like he had a wonderful heart and I wish he were here.